- PagerDuty /

- Blog /

- Incident Management & Response /

- The Four Agreements of Incident Response

Blog

The Four Agreements of Incident Response

(This blog post is inspired by the talk that I will be giving at DevOps Talks Conference Melbourne and DevOps Talks Conference Auckland. Hope to see you there!)

Have you ever been on one of those phone calls with several other human beings where you’re all almost screaming at each other while trying to troubleshoot an issue when something’s going wrong that needs to be fixed right this instant? Did you really enjoy that experience and want to do it all the time?

My guess is no.

Incident resolution can be a really tough process, but there are ways to make them less stressful—and the Incident Commander role is key.

In his book, The Four Agreements, Don Miguel Ruiz presents a code of personal conduct based on ancient Toltec wisdom that helps remove self-limiting structures and beliefs.

The Four Agreements are:

- Be Impeccable With Your Word

- Don’t Take Anything Personally

- Don’t Make Assumptions

- Always Do Your Best

Each of the Agreements can help us understand a more mature, effective, and humane approach to incident response in our organizations.The Agreements can be expressed as a modality for incident response. Using the Agreements, it’s easier to understand modern approaches to effectively resolving incidents and even help reduce burnout as well!

Be Impeccable With Your Word

Notify Stakeholders

It’s critical to keep involving stakeholders in the incident response process by giving them a way to stay updated.

At PagerDuty, we have a separate Slack room just for incident updates. It’s less noisy than our main response room and folks can get succinct updates here if they want it, provided by the Internal Liaison (who’s responsible for monitoring and updating the channel). This allows execs to stay in the loop and ask questions without affecting the main response.

Anyone Can Trigger Incident Response

At PagerDuty, anyone can trigger our incident response process. We do it with a chat command in Slack, but it doesn’t really matter how you implement this. The important thing is that you have a method to trigger your incident response process—one that’s fast, easy, and available to everyone. You don’t want to sit around, wasting time trying to figure out whether something requires response because by the time you do, you’ll definitely find a response is needed.

Don’t Litigate Severity

Don’t litigate incident severity during the call. It’s a waste of time. By the time you’re done discussing whether it’s a SEV-1 or SEV-2, it will definitely have become a SEV-2. Best practice: If you can’t decide whether it’s a SEV-1 or SEV-2, always assume it’s the higher severity option and move on.

Don’t Take Anything Personally

Switch in Mindset

Once an incident is triggered, the team needs to make a mental shift—in other words, everyone needs to change change their mode of thinking. You might consider this the difference between “peacetime and wartime” or “normal and emergency.” Things that aren’t acceptable during day-to-day operations become acceptable during an emergency.

This means that during an incident, a lot of things change. And one of those things has to do with how you communicate. It doesn’t mean you should treat each other poorly. But you should be focusing on your goal, which is to handle the situation in a way that limits damage and reduces recovery time and costs.

The Incident Commander Is the Highest Authority

If your team is following an incident response process similar to PagerDuty’s, someone will be assigned to a role called the Incident Commander (IC).

One of the most important things to remember about the IC is that they are the highest authority on the call. They are the ultimate source of truth during an incident, and no actions should take place without their say-so. This is critical to successful incident response, but it can take some getting used to. Be sure to prepare your organization for this before it happens during an incident. Don’t take this personally—it is the function of the role.

The Incident Commander Is Not a Resolver

At PagerDuty, our incident response process is based on the Incident Command System, a national model used by local, state, and federal emergency responders. In fire departments, the Incident Commander wears a white helmet to identify them as such. There is a saying that if you see someone in a white helmet pick up a wrench, take it away and hit them over the head with it.

The same concept applies at PagerDuty during an incident. (Maybe minus the hitting them over the head part.) The job of the IC is to delegate and coordinate, not do the work to resolve the incident. It’s crucial that the IC doesn’t fall into the role of a subject matter expert who is logging into servers or reviewing logs.

So while you shouldn’t be hitting your ICs with a wrench, it’s still appropriate to sometimes remind them that they should not be directly attempting to resolve the incident. If you are an IC and someone reminds you about this, don’t take it personally!

Executive Swoop

During an incident, executives may try to take over, making things more difficult for responders on the call. Addressing this is simple: Let them take over. The IC should ask, “Are you taking command of the call?” If the response is yes, then great. Most of the time, however, they won’t say anything and the team can move along to focusing on resolving the incident.

Taking this approach can be difficult as not all members of senior management will respond well to an IC who outranks them on the call. This is why it’s important to prepare senior management beforehand! Keep in mind, however, that even if this has been discussed, it can still take some adjustment.

Another thing that can happen is that an executive can demand that the incident be resolved “in the next 10 minutes.” Though this can sound really demotivating when it happens, stay professional. Say, “We are in the middle of resolving an incident. Please keep your comments to the end,” or direct them to the appropriate communication channel/liaison.

Remember that your execs aren’t trying to make things worse—they’re trying to help. Don’t take it personally.

Don’t Make Assumptions

Consensus Is Hard

Getting agreement from a large group of resolvers on a call can be tricky so you want to optimize for the majority. This is why instead of asking if everyone agrees on an action, it’s better to ask, “Are there any strong objections?” This also can prevent the hindsight effect (“I knew that wouldn’t work”), as well as emphasize that we are not looking for the most perfect solution.

Clear Is Better Than Concise

When we put in a lot of jargon (e.g., “Let’s get the IC on the RC and get some BLTs for all the SMEs”), we add a lot of cognitive overload. This also can make newcomers feel excluded. Favor clear communication rather than concise.

Assign Tasks to a Specific Person and Time-Box Them

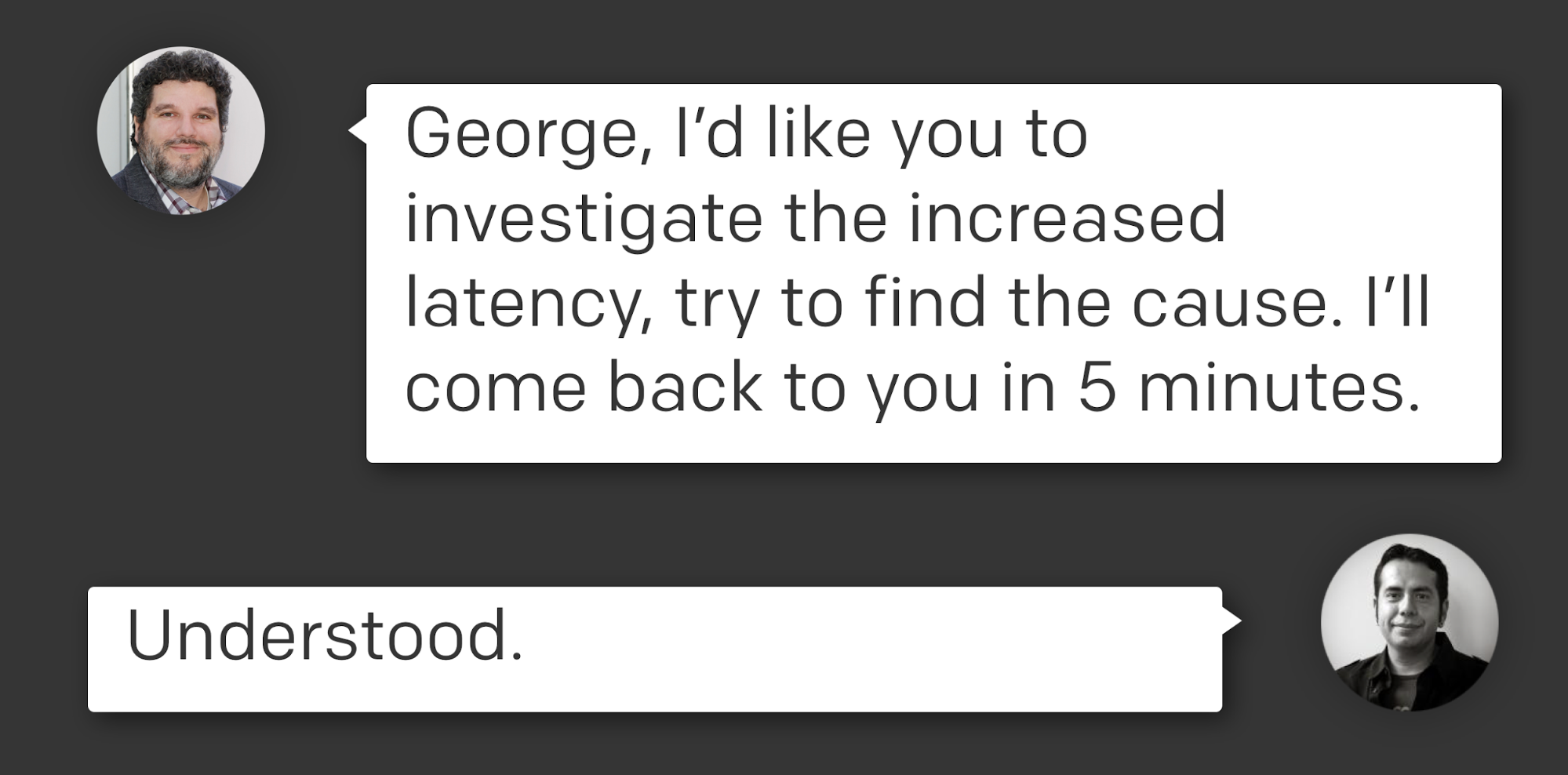

A couple of critical items to note in the above screenshot:

- Tasks are assigned to specific people, not to a group.

- Time-box tasks so that the responder knows when you will be looking for an update and doesn’t get caught by surprise.

- Make sure the assignment is acknowledged.

Following these best practices will help avoid the “bystander effect.” Remember, during an incident, the phrase “Can someone…” is deadly.

Always Do Your Best

It’s Better to Make the Wrong Decision Than No Decision

This is a really controversial statement, but remember that we change the rules a bit during an incident. Making the wrong decision will provide you with more information because you can learn from your mistakes, whereas making no decision means getting stuck in analysis paralysis.

Rally Fast, Disband Faster

Keeping resources who aren’t needed on the call can become very expensive, both in terms of money and energy. As soon as you don’t need someone, encourage them to drop from the call (you can always page them back in if you need them again). People on a call who are not actively working on the incident is stressful for the people who ARE actively working, as they know there are many folks sitting there on the line getting impatient. Keep the resources you need, but don’t be afraid to let people drop.

Handovers Are Encouraged

Do responders get tired? Do ICs get tired? Of course they do! We’re all are human. This is why we encourage handovers at PagerDuty. Handing over responsibility to a new IC is super easy: Bring the new IC in to shadow you for a little bit to get up to speed on what’s going on, and just let everyone know that a handoff if occurring. It’s really that easy.

Useful Postmortems

Whether you call it a postmortem, an incident report, or a learning review (or anything else), it’s key to perform them for every incident.

Postmortems should follow a blameless approach, but it’s also essential that your organization and team learn from them. Do more than just fill out the form. Review them. Share the stories within your organization (perhaps even outside of your team). This enhances a culture of learning and helps reduce stress. “Write-only” postmortems don’t help anyone.

For more details on how to conduct a great postmortem, check out our new Postmortem Guide.

Review Your Process

Continuous improvement is important! Whether you review your process quarterly or annually, it’s important you do so to keep improving. Make the most out of reviews by asking the right questions to ensure that your process is appropriate for your organization as you grow and mature.

For example, at a smaller organization, it might make sense to page everyone on every critical incident (for example, if you have only a small handful of engineers) and then disband the folks who aren’t needed. But this doesn’t scale as the organization grows larger, and it’s important to adapt the process. Keep asking questions about your process and don’t be afraid to refine it.

Don’t Panic

It’s very natural to want to panic during a major incident. Getting woken up in the middle of the night by alarms can be quite stress-inducing. But no matter how nervous and upset you may be getting on the inside, try your best to not let it show. Panic is contagious, and if you are showing symptoms of it as an IC, it can cause others working on the problem to panic as well. This will hamper the incident resolution process.

Act calm, and others will follow. Experienced folks will stay calm, and that can make the difference between a chaotic incident and one that resolves smoothly. So don’t panic!

What incident response best practices do your teams have? Share them on our Community forums—we’d love to hear from you!